“Active” Surfaces Control What’s on Them

Researchers develop treated surfaces that can actively control how fluids or particles move.

Researchers at MIT and in Saudi Arabia have developed a new way of making surfaces that can actively control how fluids or particles move across them. The work might enable new kinds of biomedical or microfluidic devices, or solar panels that could automatically clean themselves of dust and grit.

“Most surfaces are passive,” says Kripa Varanasi, an associate professor of mechanical engineering at MIT, and senior author of a paper describing the new system in the journal Applied Physics Letters. “They rely on gravity, or other forces, to move fluids or particles.”

Varanasi’s team decided to use external fields, such as magnetic fields, to make surfaces active, exerting precise control over the behavior of particles or droplets moving over them.

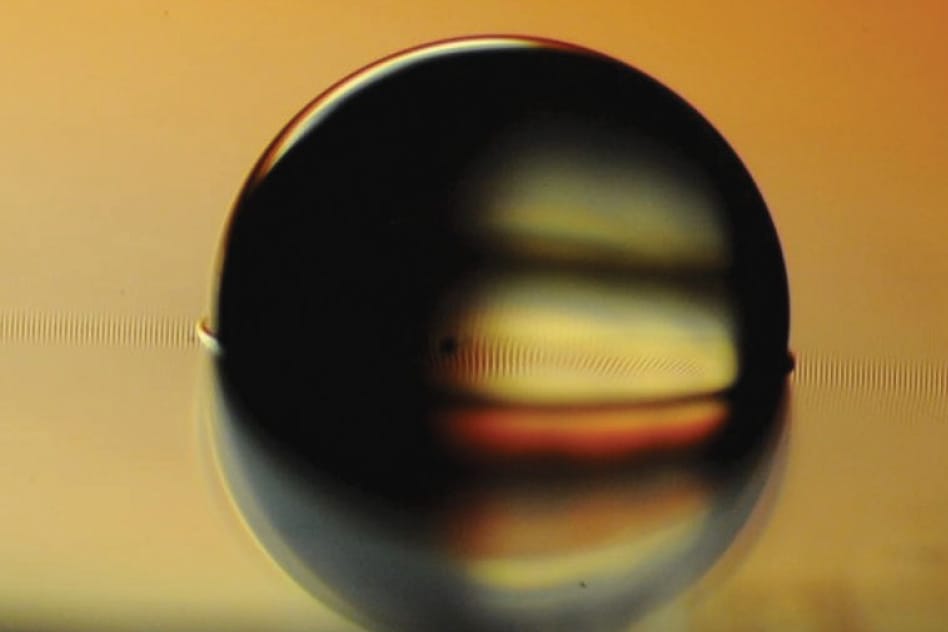

Photo shows a water droplet sitting on a ferrofluid-impregnated surface, which has cloaked the droplet with a very thin layer. Image courtesy of the researchersThe system makes use of a microtextured surface, with bumps or ridges just a few micrometers across, that is then impregnated with a fluid that can be manipulated — for example, an oil infused with tiny magnetic particles, or ferrofluid, which can be pushed and pulled by applying a magnetic field to the surface. When droplets of water or tiny particles are placed on the surface, a thin coating of the fluid covers them, forming a magnetic cloak.

The thin magnetized cloak can then actually pull the droplet or particle along as the layer itself is drawn magnetically across the surface. Tiny ferromagnetic particles, approximately 10 nanometers in diameter, in the ferrofluid could allow precision control when it’s needed — such as in a microfluidic device used to test biological or chemical samples by mixing them with a variety of reagents. Unlike the fixed channels of conventional microfluidics, such surfaces could have “virtual” channels that could be reconfigured at will.

While other researchers have developed systems that use magnetism to move particles or fluids, these require the material being moved to be magnetic, and very strong magnetic fields to move them around. The new system, which produces a superslippery surface that lets fluids and particles slide around with virtually no friction, needs much less force to move these materials. “This allows us to attain high velocities with small applied forces,” says MIT graduate student Karim Khalil, the paper’s lead author.

The new approach, he says, could be useful for a range of applications: For example, solar panels and the mirrors used in solar-concentrating systems can quickly lose a significant percentage of their efficiency when dust, moisture, or other materials accumulate on their surfaces. But if coated with such an active surface material, a brief magnetic pulse could be used to sweep the material away.

“Fouling is a big problem on such mirrors,” Varanasi says. “The data shows a loss of almost 1 percent of efficiency per week.”

But at present, even in desert locations, the only way to counter this fouling is to hose the arrays down, a labor- and water-intensive method. The new approach, the researchers say, could lead to systems that make the cleaning process automatic and water-free.

“In the desert environment, dust is present on a daily basis,” says co-author Numan Abu-Dheir of the King Fahd University of Petroleum and Minerals (KFUPM) in Saudi Arabia. “The issue of dust basically makes the use of solar panels to be less efficient than in North America or Europe. We need a way to reduce the dust accumulation.”

One advantage of the new active-surface system is its effectiveness on a wide range of surface contaminants: “You want to be able to propel dust or liquid, many materials on surfaces, whatever their properties,” Varanasi says.

MIT postdoc Seyed Mahmoudi, a co-author of the paper, notes that electric fields cannot penetrate into conductive fluids, such as biological fluids, so conventional systems wouldn’t be able to manipulate them. But with this system, he says, “electrical conductivity is not important.”

In addition, this approach gives a great deal of control over how material moves. “Active fields — such as electric, magnetic, and acoustic fields — have been used to manipulate materials,” Khalil says. “But rarely have you seen the surface itself interact actively with the material on it,” he says, which allows much greater precision.

While this initial demonstration used a magnetic fluid, the team says the same principle could be applied using other forces to manipulate the material, such as electric fields or differences in temperature.

Neelesh Patankar, a professor of mechanical engineering at Northwestern University who was not involved in this work, says this research “introduces a new class of approach for droplet-based microfluidic platforms, which have numerous applications in a variety of fields, including biotechnology.” He adds, “This work cleverly combines low-hysteresis droplet movement with low-magnetic-field-driven droplet propulsion to achieve impressive capabilities.”

The work was supported by the MIT-KFUPM Center for Clean Water and Clean Energy.