Design could enable longer lasting, more powerful lithium batteries

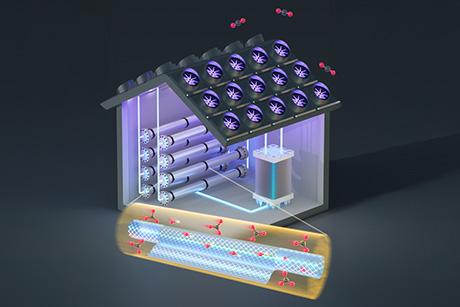

Lithium-ion batteries have made possible the lightweight electronic devices whose portability we now take for granted, as well as the rapid expansion of electric vehicle production. But researchers around the world are continuing to push limits to achieve ever-greater energy densities — the amount of energy that can be stored in a given mass of material — in order to improve the performance of existing devices and potentially enable new applications such as long-range drones and robots.

One promising approach is the use of metal electrodes in place of the conventional graphite, with a higher charging voltage in the cathode. Those efforts have been hampered, however, by a variety of unwanted chemical reactions that take place with the electrolyte that separates the electrodes. Now, a team of researchers at MIT and elsewhere has found a novel electrolyte that overcomes these problems and could enable a significant leap in the power-per-weight of next-generation batteries, without sacrificing the cycle life.

The research is reported today in the journal Nature Energy in a paper by MIT professors Ju Li, Yang Shao-Horn, and Jeremiah Johnson; postdoc Weijiang Xue; and 19 others at MIT, two national laboratories, and elsewhere. The researchers say the finding could make it possible for lithium-ion batteries, which now typically can store about 260 watt-hours per kilogram, to store about 420 watt-hours per kilogram. That would translate into longer ranges for electric cars and longer-lasting changes on portable devices.

The basic raw materials for this electrolyte are inexpensive (though one of the intermediate compounds is still costly because it’s in limited use), and the process to make it is simple. So, this advance could be implemented relatively quickly, the researchers say.

The electrolyte itself is not new, explains Johnson, a professor of chemistry. It was developed a few years ago by some members of this research team, but for a different application. It was part of an effort to develop lithium-air batteries, which are seen as the ultimate long-term solution for maximizing battery energy density. But there are many obstacles still facing the development of such batteries, and that technology may still be years away. In the meantime, applying that electrolyte to lithium-ion batteries with metal electrodes turns out to be something that can be achieved much more quickly.

The new application of this electrode material was found “somewhat serendipitously,” after it had initially been developed a few years ago by Shao-Horn, Johnson, and others, in a collaborative venture aimed at lithium-air battery development.

“There’s still really nothing that allows a good rechargeable lithium-air battery,” Johnson says. However, “we designed these organic molecules that we hoped might confer stability, compared to the existing liquid electrolytes that are used.” They developed three different sulfonamide-based formulations, which they found were quite resistant to oxidation and other degradation effects. Then, working with Li’s group, postdoc Xue decided to try this material with more standard cathodes instead.

The type of battery electrode they have now used with this electrolyte, a nickel oxide containing some cobalt and manganese, “is the workhorse of today’s electric vehicle industry,” says Li, who is a professor of nuclear science and engineering and materials science and engineering.

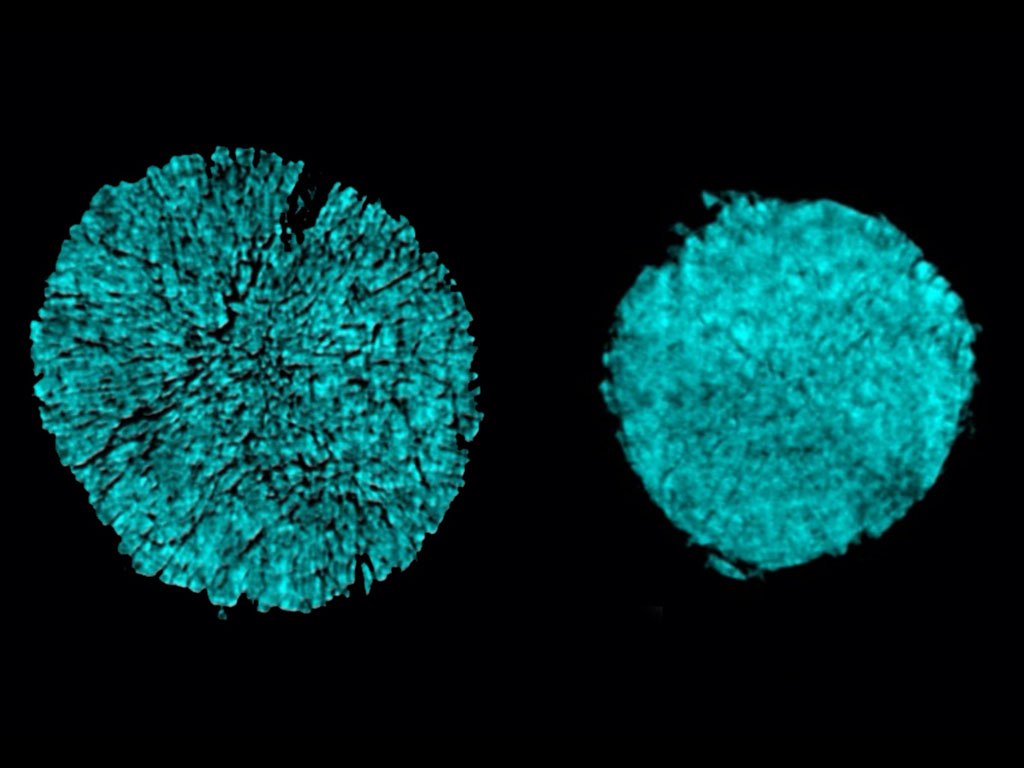

Because the electrode material expands and contracts anisotropically as it gets charged and discharged, this can lead to cracking and a breakdown in performance when used with conventional electrolytes. But in experiments in collaboration with Brookhaven National Laboratory, the researchers found that using the new electrolyte drastically reduced these stress-corrosion cracking degradations.

The problem was that the metal atoms in the alloy tended to dissolve into the liquid electrolyte, losing mass and leading to cracking of the metal. By contrast, the new electrolyte is extremely resistant to such dissolution. Looking at the data from the Brookhaven tests, Li says, it was “sort of shocking to see that, if you just change the electrolyte, then all these cracks are gone.” They found that the morphology of the electrolyte material is much more robust, and the transition metals “just don’t have as much solubility” in these new electrolytes.

That was a surprising combination, he says, because the material still readily allows lithium ions to pass through — the essential mechanism by which batteries get charged and discharged — while blocking the other cations, known as transition metals, from entering. The accumulation of unwanted compounds on the electrode surface after many charging-discharging cycles was reduced more than tenfold compared to the standard electrolyte.

“The electrolyte is chemically resistant against oxidation of high-energy nickel-rich materials, preventing particle fracture and stabilizing the positive electrode during cycling,” says Shao-Horn, a professor of mechanical engineering and materials science and engineering. “The electrolyte also enables stable and reversible stripping and plating of lithium metal, an important step toward enabling rechargeable lithium-metal batteries with energy two times that of the state-the-art lithium-ion batteries. This finding will catalyze further electrolyte search and designs of liquid electrolytes for lithium-metal batteries rivaling those with solid state electrolytes.”

The next step is to scale the production to make it affordable. “We make it in one very easy reaction from readily available commercial starting materials,” Johnson says. Right now, the precursor compound used to synthesize the electrolyte is expensive, but he says, “I think if we can show the world that this is a great electrolyte for consumer electronics, the motivation to further scale up will help to drive the price down.”

Because this is essentially a “drop in” replacement for an existing electrolyte and doesn’t require redesign of the entire battery system, Li says, it could be implemented quickly and could be commercialized within a couple of years. “There’s no expensive elements, it’s just carbon and fluorine. So it’s not limited by resources, it’s just the process,” he says.

The research was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy and the National Science Foundation, and made use of facilities at Brookhaven National Laboratory and Argonne National Laboratory.