MIT researchers 3-D print colloidal crystals

MIT engineers have united the principles of self-assembly and 3-D printing using a new technique, which they highlight today in the journal Advanced Materials.

By their direct-write colloidal assembly process, the researchers can build centimeter-high crystals, each made from billions of individual colloids, defined as particles that are between 1 nanometer and 1 micrometer across.

“If you blew up each particle to the size of a soccer ball, it would be like stacking a whole lot of soccer balls to make something as tall as a skyscraper,” says study co-author Alvin Tan, a graduate student in MIT’s Department of Materials Science and Engineering. “That’s what we’re doing at the nanoscale.”

The researchers found a way to print colloids such as polymer nanoparticles in highly ordered arrangements, similar to the atomic structures in crystals. They printed various structures, such as tiny towers and helices, that interact with light in specific ways depending on the size of the individual particles within each structure.

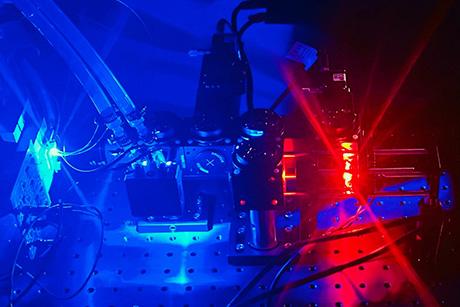

Nanoparticles dispensed from a needle onto a rotating stage, creating a helical crystal containing billions of nanoparticles. (Credit: Alvin Tan)

The team sees the 3-D printing technique as a new way to build self-asssembled materials that leverage the novel properties of nanocrystals, at larger scales, such as optical sensors, color displays, and light-guided electronics.

“If you could 3-D print a circuit that manipulates photons instead of electrons, that could pave the way for future applications in light-based computing, that manipulate light instead of electricity so that devices can be faster and more energy efficient,” Tan says.

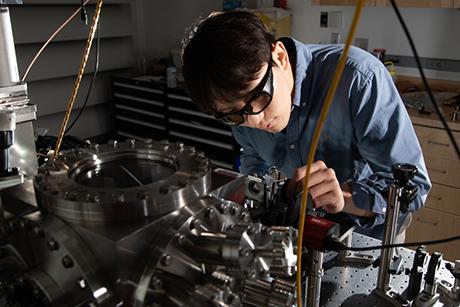

Tan’s co-authors are graduate student Justin Beroz, assistant professor of mechanical engineering Mathias Kolle, and associate professor of mechanical engineering A. John Hart.

Out of the fog

Colloids are any large molecules or small particles, typically measuring between 1 nanometer and 1 micrometer in diameter, that are suspended in a liquid or gas. Common examples of colloids are fog, which is made up of soot and other ultrafine particles dispersed in air, and whipped cream, which is a suspension of air bubbles in heavy cream. The particles in these everyday colloids are completely random in their size and the ways in which they are dispersed through the solution.

If uniformly sized colloidal particles are driven together via evaporation of their liquid solvent, causing them to assemble into ordered crystals, it is possible to create structures that, as a whole, exhibit unique optical, chemical, and mechanical properties. These crystals can exhibit properties similar to interesting structures in nature, such as the iridescent cells in butterfly wings, and the microscopic, skeletal fibers in sea sponges.

So far, scientists have developed techniques to evaporate and assemble colloidal particles into thin films to form displays that filter light and create colors based on the size and arrangement of the individual particles. But until now, such colloidal assemblies have been limited to thin films and other planar structures.

“For the first time, we’ve shown that it’s possible to build macroscale self-assembled colloidal materials, and we expect this technique can build any 3-D shape, and be applied to an incredible variety of materials,” says Hart, the senior author of the paper.

Building a particle bridge

The researchers created tiny three-dimensional towers of colloidal particles using a custom-built 3-D-printing apparatus consisting of a glass syringe and needle, mounted above two heated aluminum plates. The needle passes through a hole in the top plate and dispenses a colloid solution onto a substrate attached to the bottom plate.

The team evenly heats both aluminum plates so that as the needle dispenses the colloid solution, the liquid slowly evaporates, leaving only the particles. The bottom plate can be rotated and moved up and down to manipulate the shape of the overall structure, similar to how you might move a bowl under a soft ice cream dispenser to create twists or swirls.

Beroz says that as the colloid solution is pushed through the needle, the liquid acts as a bridge, or mold, for the particles in the solution. The particles “rain down” through the liquid, forming a structure in the shape of the liquid stream. After the liquid evaporates, surface tension between the particles holds them in place, in an ordered configuration.

As a first demonstration of their colloid printing technique, the team worked with solutions of polystyrene particles in water, and created centimeter-high towers and helices. Each of these structures contains 3 billion particles. In subsequent trials, they tested solutions containing different sizes of polystyrene particles and were able to print towers that reflected specific colors, depending on the individual particles’ size.

“By changing the size of these particles, you drastically change the color of the structure,” Beroz says. “It’s due to the way the particles are assembled, in this periodic, ordered way, and the interference of light as it interacts with particles at this scale. We’re essentially 3-D-printing crystals.”

The team also experimented with more exotic colloidal particles, namely silica and gold nanoparticles, which can exhibit unique optical and electronic properties. They printed millimeter-tall towers made from 200-nanometer diameter silica nanoparticles, and 80-nanometer gold nanoparticles, each of which reflected light in different ways.

“There are a lot of things you can do with different kinds of particles ranging from conductive metal particles to semiconducting quantum dots, which we are looking into,” Tan says. “Combining them into different crystal structures and forming them into different geometries for novel device architectures, I think that would be very effective in fields including sensing, energy storage, and photonics.”

This work was supported, in part, by the National Science Foundation, the Singapore Defense Science Organization Postgraduate Fellowship, and the National Defense Science and Engineering Graduate Fellowship Program.