New gel coatings may lead to better catheters and condoms

Catheters, intravenous lines, and other types of surgical tubing are a medical necessity for managing a wide range of diseases. But a patient’s experience with such devices is rarely a comfortable one.

Now MIT engineers have designed a gel-like material that can be coated onto standard plastic or rubber devices, providing a softer, more slippery exterior that can significantly ease a patient’s discomfort. The coating can even be tailored to monitor and treat signs of infection.

In a paper published today in the journal Advanced Healthcare Materials, the team describes their method for strongly bonding a layer of hydrogel — a squishy, slippery polymer material that consists mostly of water — to common elastomers such as latex, rubber, and silicone. The results are “hydrogel laminates” that are at once soft, stretchable, and slippery, and impermeable to viruses and other small molecules.

The hydrogel coating can be embedded with compounds to sense, for example, inflammatory molecules. Drugs can also be incorporated into and slowly released from the hydrogel coating, to treat inflammation in the body.

The team, led by Xuanhe Zhao, the Robert N. Noyce Career Development Associate Professor in the Department of Mechanical Engineering at MIT, bonded layers of hydrogel onto various elastomer-based medical devices, including catheters and intravenous tubing. They found that the coatings were extremely durable, withstanding bending and twisting, without cracking. The coatings were also extremely slippery, exhibiting much less friction than standard uncoated catheters — a quality that could reduce patients’ discomfort.

The group also coated hydrogel onto another widely used elastomer product: condoms. In addition to enhancing the comfort of existing latex condoms by reducing friction, a coating of hydrogel could help improve their safety, since the hydrogel could be embedded with drugs to counter a latex allergy, the researchers say.

“We’ve demonstrated hydrogel really has the potential to replace common elastomers,” Zhao says. “Now we have a method to integrate gels with other materials. We think this has the potential to be applied to a diverse range of medical devices interfacing with the body.”

Zhao’s co-authors are lead author and graduate student German Parada, graduate students Hyunwoo Yuk and Xinyue Liu, and visiting scientist Alex Hsieh.

A tailored gel

Zhao’s group previously developed recipes to make tough, stretchable hydrogels from mixtures composed mostly of water and a bit of polymer. They developed a technique to bond hydrogels to elastomers by first treating surfaces such as rubber and silicone with benzophenone, a molecular solution that, when exposed to ultraviolet light, creates strong chemical bonds between the elastomer and the hydrogel.

The researchers applied these techniques to fabricate a hydrogel laminate: a layer of elastomer sandwiched between two layers of hydrogel. They then put the laminate structure through a battery of mechanical tests and found the structure remained strongly bonded, without tearing or cracking, even when stretched to multiple times its original length.

The team also placed the laminate structure in a two-chamber tank, filled on one side with deionized water and the other with molecular dye. After several hours, the laminate prevented any dye from migrating from one side of the chamber to the other, whereas a layer of hydrogel alone let the dye through. The laminate’s elastomer layer, they concluded, made the structure as a whole strongly impermeable — a feature they reasoned could also prevent viruses and other small molecules from passing through.

In other tests, the team chemically mixed pH-sensing molecules into the layer of hydrogel lining one side of the elastomer layer, and green food dye into the opposite hydrogel layer. They once again placed the entire structure into the two-chamber tank and filled both sides with dioinized water.

As the researchers changed the acidity of the tank’s water, they observed that the parts of the hydrogel containing pH indicators lit up. Meanwhile, the green dye seeped slowly from the opposite hydrogel layer into the second tank, mimicking the action of drug molecules.

“We can put pH-sensing molecules in hydrogels, or drugs that are gradually released,” Parada says. “For different applications, we can modify the gel to accommodate that application.”

Tying knots

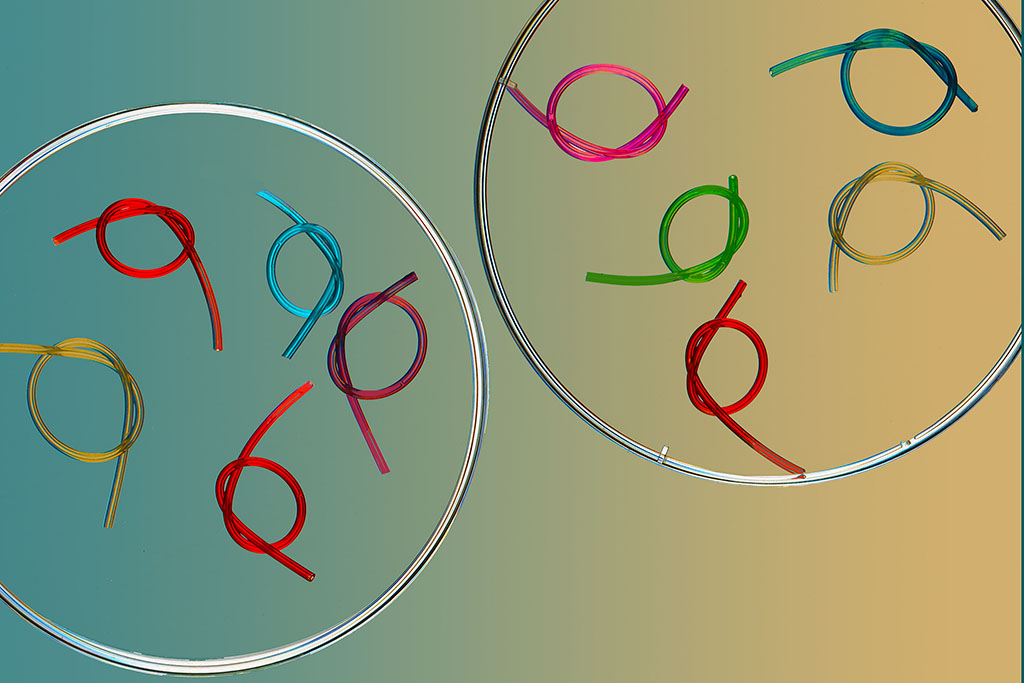

As a first foray into possible applications for hydrogel laminates, the researchers used their previously developed techniques to coat hydrogel onto various elastomer devices, including silicone tubing, a Foley catheter, and a condom.

“Our first major focus was catheters, because they are rigid and not very comfortable, and infection of catheters can cause around 50 percent of readmissions to hospitals,” Parada says. “We also thought we could apply this to condoms, because existing latex condoms cause lots of sensitivities and allergies, and if you can put drugs in the gel, you could have better protection.”

Even after sharply bending and folding the coated tubing into a knot, the researchers found the hydrogel coating remained strongly bonded to the tubing without causing any tears. The same was true when the researchers inflated both the coated catheter and the coated condom.

Parada says the dimensions of a hydrogel laminate may be tuned to accommodate different devices. For instance, scientists can choose a thicker elastomer to increase a laminate’s rigidity, or use a thicker coating of hydrogel to incorporate more drug molecules or sensors. Hydrogels can also be designed to be more or less slippery, depending on the amount of friction desired.

“We have the capability to fabricate large-scale hydrogel structures that can coat medical devices, and the hydrogel won’t agitate the body,” Zhao says. “This is a technological platform onto which you can imagine many applications.”

This research was funded, in part, by the Office of Naval Research, the MIT Institute for Soldier Nanotechnologies, and the National Science Foundation (NSF).