Using mechanical forces to improve wound healing

To most, an operating room and a manufacturing plant are as different as any two places can be. But not to Dennis Orgill.

“To some degree when you do an operation it’s much like manufacturing something in a factory,” explains Orgill SM ’80, PhD ’83, who serves as medical director at Brigham and Women’s Hospital’s Wound Care Center and as a professor at Harvard Medical School. “You want to have high quality control and be able to do it as efficiently as you can. Those engineering principles of process control are very important in surgery.”

In the early ’80s, Orgill earned his PhD in mechanical engineering at MIT through the Harvard-MIT Health Sciences and Technology (HST) program. Orgill’s particular course of study within HST was the Medical Engineering and Medical Physics program, which combines a traditional mechanical engineering education with clinical and medical exposure.

As a mechanical engineering student at MIT, it was only natural that Orgill gravitated toward the work of Professor Ioannis Yannas. Using his background in polymer science, Yannas invented the first successful method of skin regeneration in burn victims along with his collaborator John F. Burke, at the Shriner’s Burn Institute in Boston. For his PhD thesis, Orgill worked alongside Yannas to explore new methods of promoting tissue regeneration in a wound.

“Dennis is an unusually innovative person,” says Yannas. “During his PhD studies, we would have lunches together where we would formulate ideas for the next steps in making skin regeneration more effective.”

Orgill showed for the first time how to regenerate both the epidermis and the dermis of the skin. He developed a process of infusing a collagen skin graft — known as a scaffold — with healthy cells to promote regeneration. This first requires the harvesting of a healthy piece of tissue elsewhere on the patient’s body. After being mixed in an aqueous solution, the cells are then placed in a centrifuge along with the collagen scaffold. The centrifugal force helps evenly distribute the cells within the scaffold.

When applied to the wound, the cell-infused scaffold was found to promote healing even better than the original scaffold Yannas and Burke had used. Rather than just regenerating the inner layer of the skin known as the dermis, these new cell-seeded collagen scaffolds promoted regeneration of the outer epidermis layer of skin at the same time.

After earning his PhD through HST, Orgill obtained his MD from Harvard Medical School. Over the course of nearly three decades working at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Orgill has continued his focus on finding ways to make wounds heal better.

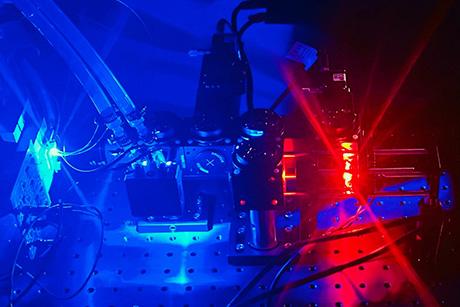

“My group has been conducting research on how mechanical forces are helping wounds to heal,” he says. “The concept of combining cells with the scaffold and adding mechanical forces is going to be a powerful way to move forward with skin regeneration.”

Orgill’s medical research and practice have both been informed by his mechanical engineering background. “During my PhD program, I took various classes in subjects like finite element modeling and heat and mass transfer,” he explains. “These principles are incredibly important when looking at thermal burns and cooling devices.”

Orgill says examining medical problems through an engineer’s lens has made him a better surgeon. “Mechanical engineering teaches a thinking process of how to analyze and tackle problems — in surgery we think in an analogous way,” he says.

Orgill thinks in the future, operating rooms will be filled with more doctors with engineering degrees. The growing number of biomedical engineering programs offered at universities seems to confirm this trend.

“I think people will recognize that medicine is going to be better if we have more engineering incorporated into it as a way of thinking,” says Orgill. “That’s how we can solve quality, efficiency, and cost problems in the medical field.”